The Week in Research Review, etc 7-29-18

Last week was the 1st of my research review that summarized my social media posts from the previous week. It seemed to be well received so I figured I’d continue it. My goal is to help summarize some of the research that I found interesting and package it nicely for my readers.

Each photo contains a link back to a social media feed where you can see the conversation that ensued and maybe chime in…or just be a passive reader and see where the conversation went. You never know where the conversation may go on social media…so be ready! haha!

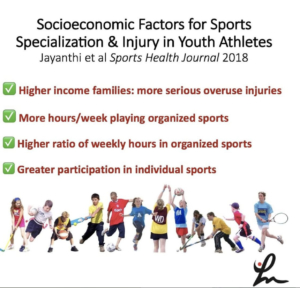

Socioeconomic Factors for Sports Specialization and Injury in Youth Athletes Jayanthi et al Sports Health Journal 2018.

This study looked at the effect of socioeconomic status (SES) on rates of sports specialization and injury among youth athletes.

They looked at injured athletes between the ages of 7 to 18 years that were recruited from 2 hospital-based sports medicine clinics. They compared these with uninjured athletes presenting for sports physicals at primary care clinics between 2010 and 2013.

They concluded that:

✅High-SES athletes reported more serious overuse injuries than low-SES athletes

✅More hours/wk playing organized sports

✅Higher ratio of weekly hours in organized sports to free play

✅Greater participation in individual sports

I applaud the authors for attempting to bring this very difficult collection of data into a formal research paper. I will say some of the statistics and standard deviations may not make the conclusions as powerful.

I do think this is a good paper to help educate our athletes on injury rates, especially in those that specialize in 1 sport.

What do you think? Tag a friend that may benefit from this article!

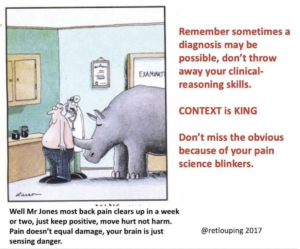

From #Twitter’s @retlouping that perfectly sums up what I’ve observed recently on social media with many PT’s.

For some reason, pain science has overtaken most diagnosis and treatment conversations.

It’s as if you get bullied into talking pain science and ignoring our clinical judgment and diagnosis skills. I understand there’s a constant tug-of-war between the biomechanical PT’s and the pain science PTs.

But as usual, the answer usually lies somewhere in between and both groups are correct. The biomechanics of an injury are often important as well as the language we use to explain these tissue biomechanics.

To my fellow clinicians, especially the newer grads and #dptstudent, remember this little cartoon for every future encounter.

Yeah, speak to people in non-threatening tones (in my world it’s just being respectful) but trust me, they WANT to hear what could be going wrong or what may be causing their pain.

Don’t blow off their symptoms and don’t go into depth about pain science because they won’t understand.

Trust me, the clinicians that try to do that often end up losing their patients in the long run.

I hear these stories day after day of people coming to me because the last PT either only talks to them or made them ONLY do strength exercises and it didn’t help their pain.

The PT didn’t listen to them and was so blinded by their pain science background that they ignored the person sitting right in front of them. Remember, the person sitting there will tell you what is going on and what treatment will most help them feel/move better.

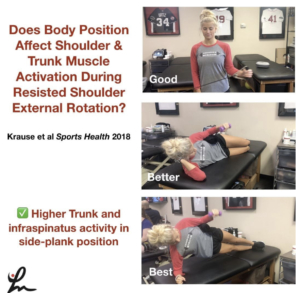

Influence of Body Position on Shoulder and Trunk Muscle Activation During Resisted Isometric Shoulder External Rotation Krause et al Sports Health 2018.

The purpose of this study was to examine ER torque and electromyographic (EMG) activation of shoulder and trunk muscles while performing resisted isometric shoulder ER in 3 positions:

✔️Standing

✔️Side-lying

✔️Side plank

Using surface EMG and a hand-held dynamometer, the researchers tried to determine EMG activity of the:

✔️infraspinatus

✔️Posterior Deltoids

✔️Mid traps

✔️Multifidi

✔️External/internal obliques (dominant side)

✔️External/internal obliques (non-dominant side)

EMG values for the infraspinatus were greatest in the side plank position. In general, EMG values for the trunk muscles were also greatest in the side plank position.

✅Their Conclusions: If the purpose of a rehabilitation program is to strengthen the rotator cuff, in particular, the infraspinatus, the side plank is preferred over standing or side lying. If the goal is to simultaneously strengthen both the rotator cuff and trunk muscles, the side plank position again is preferred.

Makes sense but good to see the research and have concrete evidence to back up what we think actually goes on.

Tag a friend who may be interested in this research paper!

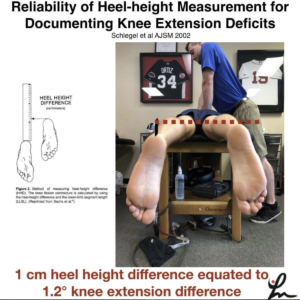

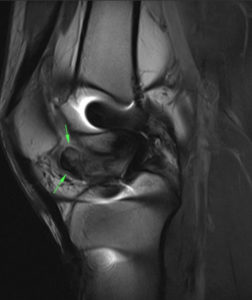

Reliability of heel-height measurement for documenting knee extension deficits. Schlegel et al AJSM 2002

Prone heel-height difference of 1cm equates to 1.2 degree difference in knee extension ROM.

Do you use this method to assess knee ROM? I still measure knee extension ROM is supine but find this method helpful as well.

I know my friend and colleague @wilk_kevin has measured this way for many years. i originally saw his use this technique at @ChampionSportsM

I don’t want people to confuse this with prone hangs for knee extension ROM. I am not a fan of that method as I’ve stated in the past.

This is a method to assess knee extension differences, particularly after an ACL reconstruction. I have gone back to using this method for some people that have subtle ROM differences side-to-side.

The patella position (on the plinth or off) did not matter in the study and thigh girth did not appear to make a difference.

I would recommend stabilizing the pelvis to prevent excess ROM from occurring at that region and to better isolate the knee joint.

Have you tried this method? Tag a friend who may benefit from using this ROM method…thanks!

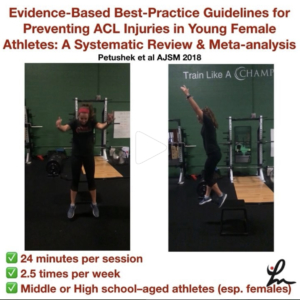

Evidence-Based Best-Practice Guidelines for Preventing #ACL Injuries in Young Female Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Petushek et al AJSM 2018.

Injury prevention neuromuscular training (NMT) programs reduce the risk for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury.

Eighteen studies were included in the meta-analyses, with a total of 27,231 participants, 347 sustaining an ACL injury.

The overall mean training amount was 57 sessions totaling 18.17 hours (roughly 24 minutes per session, 2.5 times per week).

They concluded:

✔️Interventions targeting middle school or high school–aged athletes reduced injury risk to a greater degree than did interventions for college or professional-aged athletes.

✔️Continued exposure to neuromuscular training throughout the sport season seems to enhance prophylactic effects of NMT.

✔️NMT interventions were effective for female basketball, and handball athletes and interventions including various athletes were potentially effective (eg, soccer, basketball, and volleyball).

✔️ Interventions included some form of implementer training (eg, instructional workshop, video, or brochure) on proper program implementation.

✔️Programs including more landing stabilization and lower body strength exercises during each session were most effective.

🤔Programs including balance, core-strengthening, stretching, or agility exercises were no more effective than programs that did not incorporate these components.

✔️ Specifically, programs that included more landing stabilization exercises (eg, drop landings, jump/hop and holds), hamstring strength (eg, Nordic hamstring), lunges, and heel-calf raises reduced the risk for ACL injury to a greater degree than did programs without these exercises.

✅ Wow, lots of great information here. Please share this with a friend or colleague who may benefit from knowing this information.

Hope that helped to catch you up on my posts from this week.

Do you like these weekly updates? Let me know if I should continue…love your feedback!

Thanks for reading!